First Hundred Years

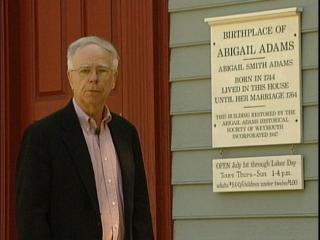

Theodore G. "Ted" Clarke was a member of the Weymouth Historical Society, Chair of the Historical Commission, and wrote and appeared in several television programs about Weymouth's history. In 2005, he wrote “Weymouth History,” which was published by the Weymouth Historical Society. He also wrote a weekly column for the Weymouth News about the town’s people, history, and significant places. Mr. Clarke passed away on September 4, 2017.

Part I

Most of you know that Weymouth was the second settlement in Massachusetts. But there’s a lot more to its beginnings than just that stale fact. This will be a quick tour through our town’s early history. We’ll introduce you to some situations the early settlers faced, the kinds of decisions they made, and what those beginnings meant to the town we have today. This will give you a passing glance at the first 100 years of our town. In later programs we’ll see what happened after that.

Early Weymouth is an excellent example of a group of people who made their own rules and laws, governed themselves, and took advantage of the things they found at this inlet of Massachusetts Bay. The first group who settled there were not the ones who made these things happen. They did locate an excellent spot for the town to grow in, but they were not prepared to get along with their neighbors, to take care of themselves, or to leave a heritage for those who came after. From the second group of settlers, only a few had a major impact on the future town. But both of these groups left an ember of life that grew into a colonial settlement and then a town. The resilience and self-reliance of these early people led to the Weymouth we know today.

But these people weren’t just names in a history book. They were humans just like us. So, like us, they did some things well, and some things poorly. When they came up against problems they couldn’t search the internet or get on the phone for a solution. They had to find their own. Let’s take a look at how the early settlers succeeded and how they failed, and let’s see how the town built upon these early foundations.

1622 is the date of the settlement of Weymouth, then known as Wessagusset. It came only two years after the Pilgrims had settled in Plymouth and is the second-oldest settlement in Massachusetts. But unlike the Plymouth settlement, Weymouth was settled according to a plan. It had nothing to do with religious freedom. It had everything to do with making money. And the choice of Weymouth was based on its geography. In fact, a lot of Weymouth’s history grew right out of its geography – where it is on the map, what the land and the coast and the rivers are like, and where it’s located in regard to Boston and the rest of the world.

So we ought to look at the geography first in order to understand why things worked out the way they did. At the same time, we have to keep an eye on the rest of Massachusetts – the things that were happening in Boston and Plymouth and Salem and other early settlements. They all had an effect on what the colonists were doing in Weymouth during the same period.

Weymouth is on the seacoast, but it’s in a harbor that’s protected by island barriers and by the peninsula of Hull from ocean waves and storms. It was and is a good place to dock wooden sailing ships without worrying about having them dashed to splinters on the rocks.

That same harbor has the mouths of two rivers – the Fore River and the Back River. Both were deep enough for sailing ships and each had some rapid or falling water that could be used for power, but they also had protected inlets where you could tie up a boat or build a mill or fishery.

And, yes, fish were important and so were shellfish. That goes back to the early days of the American Indians who had been fishing and trapping and trading along these shores for thousands of years. In fact, in the time just before white settlers came, the American Indians of the Massachusetts tribe spent summers here doing those things. Each winter they went to their year-round villages in the Blue Hills.

(In 1965, a dugout canoe was found in Great Pond after the pond had become shallow because of a drought. The canoe was brought to the Tufts Library where carbon-14 testing found it to be 600 years old. Other Indian artifacts were also found, mainly around the ponds and streams of the town. Some of these relics date back thousands of years.)

As it happened, there had been an outbreak of serious disease about five years before the settlement and it had killed many Indians near the coast of Massachusetts, in and around Massachusetts Bay. That event had something to do with the choice of Weymouth for settlement.

That brings us to choice. How was Weymouth chosen? The settlement was spurred by Thomas Weston from London, England. Weston was not interested in religious freedom like the Pilgrims or Puritans. He didn’t care much about setting up a colony for future generations either. No, Weston was a money man. They were called “merchant-adventurers” then. He was one of a group that had helped to finance the Pilgrims and helped pay the cost of the “Mayflower”. But Weston expected things in return. He wanted the Pilgrim settlers to send back to England timber and beaver skins and fish.

But the Pilgrims weren’t very interested in those things, so it wasn’t long before he lost interest in them. When he made additional demands on them, the partnership teetered and eventually collapsed. He sold his shares in the Plymouth company in May 1622. But even though Weston was not interested in the religious leanings of the Pilgrims, he did believe that a New England settlement could make money. So he decided to form his own company and his own settlement.

He obtained a grant to 6,000 acres of land in Massachusetts Bay and bought two ships – the “Charity”, 100 tons, and the “Swan” – 30 tons, as well as a smaller vessel – the “Sparrow”. Weston had learned about the New England coast from those who had been there. He also had a map made by John Smith in 1614 which included Boston Bay, and what is now Weymouth. Smith had described the region as the “Paradise of New England.” That sounded good.

But stories and maps can only tell you so much. Weston wanted better intelligence. So, early in 1622 he sent the “Sparrow” to New England to check things out. It stopped first at the fishing station along the Maine coast at Damariscove Island. From there a few men took a smaller boat, called a shallop to explore the coast. They were looking for a good place for a trading post and they found an excellent area along the Fore River in Massachusetts Bay called “Wessagusset” in the Indian tongue spoken there. But they wouldn’t hear from too many Indians because of that epidemic we told you about that had wiped out much of the population a few years before. Not having large numbers of Indians around was all right with this group.

They also liked this area for just the reasons we talked about earlier – location, location, location. On the coast, but protected; – rivers with inlets and power; – fish and shellfish. It also had marsh grass that could be harvested, and open lands that could be settled without their having to go to the trouble of cutting down lots of trees.

So they agreed. This was it. As planned, they now sailed south to Plymouth. It happened that they arrived just in time to save the life of the Indian named “Squanto” who was suspected of helping to plan an Indian raid on Plymouth. Squanto was about to be executed. After the distraction caused by the Sparrow, Squanto was found to be innocent. There are many stories about Squanto, but that’s for another time and place.

Meanwhile, Weston had sent over his two other ships, the Charity and the Swan. They reached Plymouth in June. The Charity went on to Virginia, while a few of the 60-70 men in the Swan, led by Weston’s brother-in-law, Richard Greene, left for Wessagusset where they were welcomed by the Indians and their sachem Aberdecest. They exchanged gifts and made arrangements with the Indians to give them the right to settle there. They chose a site for their settlement where the Fore River meets the Monatiquot, a place later called Hunt’s Hill.

It was described as land that projected into the water, with a curving point. When they passed around it they came to a beautiful bay sheltered from wind and waves. Here they anchored and stepped ashore.

History is often uncertain. Documents are lost. Accounts vary. People interpret the same data differently. We’ll find several cases like that in our history of Weymouth. One of them is a long-standing doubt about where Weston’s men landed. But in 1884 a map of Massachusetts Bay drawn by Governor Winthrop in 1634 was located. This map actually shows the site of the Weston settlement at Hunt’s Hill between the present location of the Fore River Bridge and the foot of Sea Street. The “beautiful bay” would have been what we call King’s Cove. It was probably more beautiful then.

So it was on Hunt’s Hill (which is no longer there) that the settlers built a blockhouse for protection, houses to live in and the other buildings they needed. Those of Weston’s men who had been left in Plymouth went on to Wessagusset in late summer. And they were all men – no women, no families. That was what Weston wanted. They were said to be 30 servants and 30 gentlemen, but both the number and the type of men is uncertain. These men were not prepared to be colonists. They did not know how to take care of themselves in an undeveloped land. In particular, they failed to provide a storehouse of food for the cold weather to come. They existed hand-to-mouth, using up the fish and other food they acquired and saving nothing for later on. They built a fort and huts, but they had no skills and no provisions for hunting, planting, or fishing. You’ll remember that the Pilgrims had Squanto to teach them these things. Weston’s men had no such help. Some starved. In “A Voyage to New England”, (written at that time) Christopher Levett said they went about to build Castles in the Aire. His opinion may have been on solid ground.

Once they realized they were in trouble, the Wessagusset men joined with the Plymouth settlers for some foraging and trading expeditions, and they did bring home some food. But by late winter, they ran out again. They then turned to the Indians and here again, they failed in their dealings. They traded for corn, giving up clothes and blankets or performing services for them like cutting wood. This did not gain them respect, and when some of them began to steal corn from the Indians, things got worse.

When one of them was caught stealing, the Indians demanded that they punish him. (The punishment would have been hanging.) However, the thief was a tall, strong young man – one of their best workers, and a cobbler, too – and therefore very valuable to them.

They held a trial. Some of the settlers wanted to take a sickly, dying man who was a weaver, and dress him in the clothes of the thief and hang him instead. But in the end (depending on which version you accept) the true thief was hanged. If he was not, it wasn’t an auspicious moment for justice in America. Whoever they hanged, it did not settle the problem.

The current leader at Wessagusset, John Saunders, wanted to steal food from the Indians, but the people of Plymouth talked him out of it. He then left for the Maine fishing villages by shallop to get food there, but was not heard of again at Wessagusset. It has since been learned that he stayed in Maine. After Saunders left, food became even more scarce. Ten settlers in all died through hardship or disease.

Accounts vary markedly about the event which brought this difficulty with the Indians to an end. It is clear that relations with the Indians worsened. The Weston people strengthened the stockade.

In any case, the Indians, particularly one called Wituwaumet and one called Pecksuot, either threatened or appeared to be threatening not only the Wessagusset settlers, but those of Plymouth as well. There had recently been a massacre of settlers by Indians in Virginia, and news of this event had reached the settlers at Wessagusset and Plymouth as well as the Indians of the area. As you can imagine, that made the settlers jittery and more wary of Indians. The news may also have emboldened the Indians who had been afraid of the firearms the white settlers carried.

Phineas Pratt, now a leader of the Wessagusset contingent, believed from the actions of the Indians that they were planning an attack, both there and at Plymouth when the snow melted. He decided to go to Plymouth on foot by night to warn that colony. The account in his diary of his trip by foot is harrowing. He believed he was followed by an Indian who lost his track because Pratt stayed away from snow and mud where he would leave footprints. However, when he arrived at Plymouth, he learned that his news was no news at all. The Pilgrims had already heard of the plan for an attack from the sachem Massasoit. The chief had told this to a Plymouth settler who had given him medical treatment.

Not only that, but the Plymouth group had already discussed the situation and had agreed to take action. They sent Myles Standish and eight other armed men via boat to Wessagusset. Standish had met Wituwaumet earlier and had considered some of the Indian’s words to him to be threatening and insulting, so he was ready to take action. According to one version, when he arrived, Wituwaumat and Pecksuot visited Standish inside the stockade where Wituwaumet warned of destruction and the two Indians taunted Standish about his short stature.

Accounts of the skirmish that came the next day, April 6, 1623, differ somewhat. Apparently Standish lured Pecksuot, Wituwaumet and some others into the stockade for a feast. (One writer has said the food was drugged.) Five whites and four Indians were present. Standish had hoped for more Indians, but the two strongest fighters were there so he proceeded with his plan.

At a signal the doors were closed and Standish grappled with Pecksuot and wrested his knife from its sheath, at last killing him with it. Wituwaumet was also killed as was one other Indian, and the remainder of the Indians were routed. Wituwaumet was beheaded and his head was taken to Plymouth where it was displayed at the fort as a warning.

After this, however, at Standish’s advice, most of the Wessagusset settlers went to Plymouth or to the fishing stations on the Maine coast. According to Pratt, three remained at Wessagusset and were killed by the Indians.

Part II

To the southeast of Hunt’s Hill was Hunt’s Plain. The two were separated by a ravine (often called a “sneak-through) used by Indians. Hunt’s Hill was the base in the early 1700s of a joint stock company in the fishing trade. As of 1876 it was the location of a shipyard operated by N. Porter Keene. However, it was cut down for landfill in the making of Marine Park in South Boston at Castle Island, and is no more. The history of this early period is recalled in many of the street names in North Weymouth like Pecksuot, Wituwaumet, Standish, Hobomock and of course Wessagussett.:

Shadows of the past return, however. A study by G.S. Lord brought to life written statements from the Wessagusset Colony. Some are interesting:

“Hunt’s Hill, which is now known as the Site of the Weston Colony, was a ridge of glacial origin projecting into Fore River Bay at the Mouth of the Monatiquot River and rose to a considerable height. It was divided into two sections by a sort of gully or small ancient (glacial) channel which was given the name of “ravine,” and played an important part in some events of Weymouth history.”

And: “In one case a man, who was weak from the want of food, was caught in the mud, and not being strong enough to pull himself out was drowned when the tide came in.”

(In June 2004, a man was found drowned on the shore of Weymouth Neck near the present Weymouthport. He was stuck in the mud and standing upright. No foul play was believed to be involved.)

Skeletons uncovered near the foot of Sea Street are believed to be from the days of the Wessagusset colony including those of Pecksuot and Wituwaumet. Two headless skeletons were unearthed in the early 1800s when the cellar was dug for a house at 236 Sea St. These bones are interred in the tomb of the owner of that house (Edward Blanchard) at North Weymouth Cemetery.

In the early 1900s a house was built over the tomb of the first colony at 43 Bicknell Road, near the Fore River. Seven skulls were found. The owners placed five of the seven skulls into a wall in the cellar. A later owner and her children, who had just moved to Weymouth and bought the house, reported being awakened at night to see a giant Indian (Pecksuot?) glowering at them. This family had not known of the earlier discovery of skulls.

Capt. Robert Gorges

Six months after the killings at the fort, in September, 1623, the settlement was occupied again by Capt. Robert Gorges, son of Sir Fernando Gorges the New England explorer of earlier years, and several families. (Gorges held a grant from the government.)

About 120 passengers arrived from Weymouth, England in the “Katherine” and the “Prophet Daniel”. They included both men and women in an effort to start a real colony. The weather off the coast of Massachusetts was stormy with cross winds and they were forced to seek shelter at Wessagusset, farther south than they had planned.

They took possession of the Wessagusset plantation, and may have added buildings since they were a larger group. Gorges was a member of the Church of England, and in the party were two ministers – Rev. William Morell and Rev. William Blaxton.

Gorges’ stay, too, was short-lived. He received a message from his father back in England, advising his son to return home. There was bad financial and political news Gorges and some of his settlers returned to England in the spring of 1624. But some of the Gorges group, along with some of the Weston people who had been in Plymouth continued the settlement at Wessagusset.

Others left Wessagusset later: The Rev. Morell went back to England in 1625 and Rev. Blaxton (or Blackstone) became the first settler of Boston until the Puritans arrived. Samuel Maverick, who arrived with Gorges) built a house at Winnisimmet, which is now Chelsea, and later was granted Noddle’s Island (East Boston). Thomas Morton, who had been in Wessagusset and returned to England, settled Mt. Wollaston (later Braintree and now Quincy).

There were enough people remaining at Wessagusset to perpetuate the colony, and others arrived in small numbers over the next several years. Meanwhile, other settlements were being made along the coast of Massachusetts including at Cape Ann and Dorchester. Salem was settled by a Puritan group in 1628 and Boston by another in 1630.

By the time Boston was settled, about 300 people were living in and around the settlement at Wessagusset. At that time, Wessagusset was recognized as part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, seated at Boston, and in 1632, Governor Winthrop of Boston visited Weymouth on his way south. That same year that the governor visited, a tax was levied by the General Court at Boston. Wessagusset had to pay five pounds as opposed to eight for Boston and four for Salem.

Weymouth Becomes A Town

Wessagusset became incorporated as “Weymouth” in 1635. In that year, Rev. Joseph Hull came from Weymouth, England on the “Assurance” with 21 families and was given permission by Mass. Bay Colony in Boston to “sit” (reside) in Weymouth. This number of new people, gave assurance that the settlement would remain. The infusion of population was such that in September it became a plantation called “Weymouth”. There were sufficient numbers who had originated in Weymouth, England to make that name a logical choice. The first representative to the General Court (legislature) in Boston was named – William Reade, a tailor. Many prominent families of today’s Weymouth had ancestors among the Hull company

One of the unique facts about early Weymouth was that it was governed by the people themselves. Unlike Plymouth, Boston and Salem, all of which had governors, Weymouth had none. So all decisions were made by the settlers gathering together in town meeting style. That type of town government has continued to the present day in many places in New England. But it all started here. When Weymouth was incorporated as a town in 1635, it was under that form of government.

According to historian Charles Francis Adams: “…for those Towns there was no prophet, no chief, no lord, no bishop, no King. Those dwelling in them were all plain people. They stood on their own legs, such as they were; and there was no one to hold them up.”

The next year, boundaries were set with Quincy (then “Mt. Wollaston”) using the Fore River and Smelt Brook, and with Hingham (then “Bare Cove”) using the Back River and Fresh River. Grape Island and Round Island were made part of Weymouth.

In 1635 Thomas Applegate of Weymouth was licensed to run a ferry between Wessagusset and Mt. Wollaston. The boat was used to transfer salt, which was taken from the marshes. Marsh grass was also dried and used to thatch roofs of the huts. Seaweed was useful, too. The early settlers packed it along the base of their houses to keep out the cold in winter in what was an early form of cheap insulation

The early settlers not only fished and gathered shellfish, they also raised grains and vegetables and kept animals. Since the area was wooded, lumber became a good business. The rivers and harbors made it possible to dock ships p and send the lumber to other places. But as trees became scarce, laws had to be made about cutting them down.

Separation of Church and State?

We said in the beginning that the original settlers did not come for religious reasons. Subsequent groups, however, brought ministers, including Rev. Hull, so early Weymouth must have had religious services. The year book of the Old North Church at Weymouth Heights states that the church was “Gathered in 1623”. We know that a meetinghouse was built on Watch Hill where the present North Cemetery is, opposite the Soldiers Monument. It was replaced by another built in 1682.

However, several Protestant sects were represented in those early days, and they didn’t always get along. Many were Church of England, some were Puritans, and some of other persuasions. Most of the ministers favored the Church of England, but no sect was completely dominant. As newcomers came into Weymouth, the struggle became more intense. There are even cases of men being fined for disturbing the churches. An era of religious persecution of Quakers, Baptists and Episcopalians began, and it became dangerous even to have an English Prayer Book in your hand.

The Pilgrims at Plymouth and the Puritans at Boston did not agree at all about religion, and both were opposed to the rituals of the Church of England, so each applied pressure on Weymouth to follow their religious beliefs. This had the effect of stifling growth in Weymouth and causing many in town to go elsewhere where they could worship without pressure.

Weymouth was seen by the Puritans as the hotbed of the Episcopal Church (Church of England). Their worship was called “Popery” for its rituals that looked similar to those of the Catholic Church. Puritan leaders were determined that it must be stamped out. A committee from Boston was sent to Weymouth to search out and put an end to this form of worship”. Those who favored the Church of England were punished, fined, whipped or driven out of town. Freedom of speech and religion were crushed.

A curious example of this fever has come to us. Governor Endicott, a puritan minister, was so opposed to “Popery” that he cut out the cross from the flag because he considered it a symbol of Popery. (In 2004, the state of California was forced to remove the cross from its flag by those who believe it violated the separation of church and state. So symbols remain important, and religious struggle continues.)

In 1642, citing “land shortage” some of the residents of Weymouth moved to Rehoboth on the Rhode Island border with their minister, Rev. Samuel Newman. Many writers believe the move came because of religious differences, and that certainly seems logical. Weymouth historian Gilbert Nash says that Newman, who remained in Weymouth for four years, “…could not easily become reconciled to the spirit which was fast growing in Weymouth, so he resolved to emigrate….” Newman, an Episcopalian, took about 40 families with him. He was moving to an area where William Blaxton (formerly of Wessagusset and Boston) was now living. Others such as Roger Williams and Ann Hutchinson, driven out of Boston by the Puritans, would also migrate to the Rhode Island area. Blaxton said he left England to “…get away from the power of the Lord’s Bishops, but he left Boston to get away from the power of the Lord’s Brethren.”

Growth and Separation

In 1637 came the Indian War called the Pequot War for which Weymouth provided five men. In that year an order came down from the General Court that no dwelling house should be built more than a half mile of the meetinghouse (church). That order was made for fear of Indian attack, but it was not enforced in Weymouth where people had by that early date spread out from King’s Cove to Watch House Hill, a mile away, and up over King Oak Hill and as far away as Whitman’s Pond.

Though town meetings were held in some form from early days, formal records of these began in 1641. The following year the Indian title was purchased, as mentioned in the records, and in 1648 we find the earliest of many references to the “herringe broge” (Herring Brook). As of 1651, two town meetings per year were required.

History is easier to write when you have official records like reports of town meetings, but there can still be disputes. Today’s historians disagree about events as recent as World War II – did Roosevelt know about Pearl Harbor ahead of time? They disagree about Iraq – did Bush know there were no weapons of mass destruction ahead of time? It isn’t surprising then that we find disagreement from the days when written records were sketchy.

Still, looking at early records can be quite interesting, and can give you some of the picture as to how things were. Examination of early town meeting records shows that human nature has not really changed over the years judging from the various complaints against people for violating their neighbors’ rights or the laws townspeople had made collectively.

The records also give an indication of how the town was run. For example, church and town were clearly joined as shown from a 1682 vote to form a committee to consider whether to repair or replace the old meetinghouse (church). The committee took only three weeks to recommend replacement due to rotting wood and the need for more space and light. Town meeting agreed with their recommendation and the work began at once. Though human nature may be the same, this kind of speed in government action may be a “thing of the past” – a relic.

A more widespread Indian War began in 1675. It was known as King Philips War and on February 12, 1675 several houses were burned in Weymouth and settlers were killed. The following year, houses and barns were burned in a raid, and a month later a Weymouth resident was killed in an attack. The people of Weymouth lived in fear because many of their men were away fighting along the Connecticut River.

According to tradition, fights between settlers and Indians took place on White’s Neck (now Idlewell) near Mill Creek, at the base of Cemetery Hill, near the Great Swamp on Neck Street and one on Middle Street near Whitman’s Pond – perhaps not far from where you live now.

By 1700 what would become the town’s major industry for over 100 years had its early beginnings. Shoemaking was being carried on by cobblers who went from home to home to make shoes. Usually they would stay for several days, measuring the feet of each person in the house and making the shoes with leather they got from a local tannery. The shoes were very basic. In a future video we’ll give you more details.

Let’s close out this one by mentioning a split of another kind that was happening in Weymouth. This time it wasn’t along religious lines, though it did involve the church. With a town as many miles long as Weymouth, it was difficult to get from one end to the other, particularly when the roads were merely trails, and especially when the weather got bad. But everybody was expected to be at the meetinghouse in the north end of town every Sabbath and holy day. At least until 1721.

At that time, a second meetinghouse was built in the south part of town. Of course this required a minister. And who should pay for him? In these days of separation of church and state, it’s hard to contemplate such an issue, but for our ancestors it was a real question. The town was paying for the minister in the north of town, but the people who lived there evidently thought local. The south part of town was not in their backyard, and they didn’t want to pay for the minister. So, those in the south part of town petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to become a new precinct or township. The north opposed it, and town meeting voted:

“To appoint John Torrey to represent Town at General Court in opposing any effort to divide Town or support two ministers from out of Common Funds.”

However, the second precinct was created in 1723 and a minister was appointed. There were later attempts to divide the town into two towns, but none were successful. So at the end of 100 years, Weymouth was one town with two precincts, its major religious battles were presently behind it, it was growing slowly, and the beginnings of early industry were starting to pop up.